History of the S.S. Rossland

Fastest Sternwheeler on the Inland Waters: The History of the S.S. Rossland

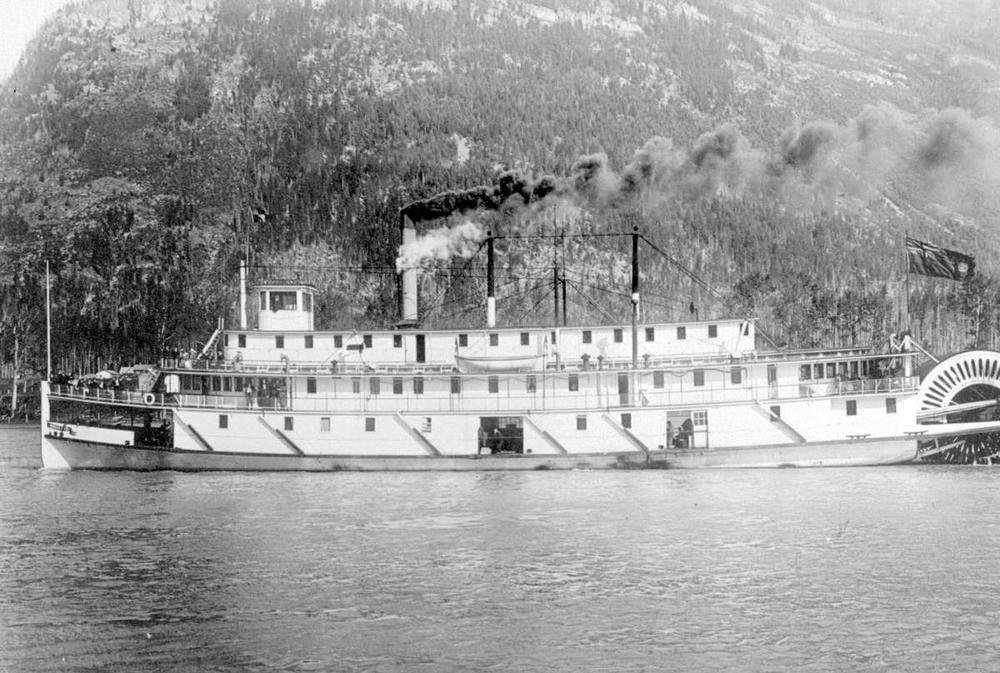

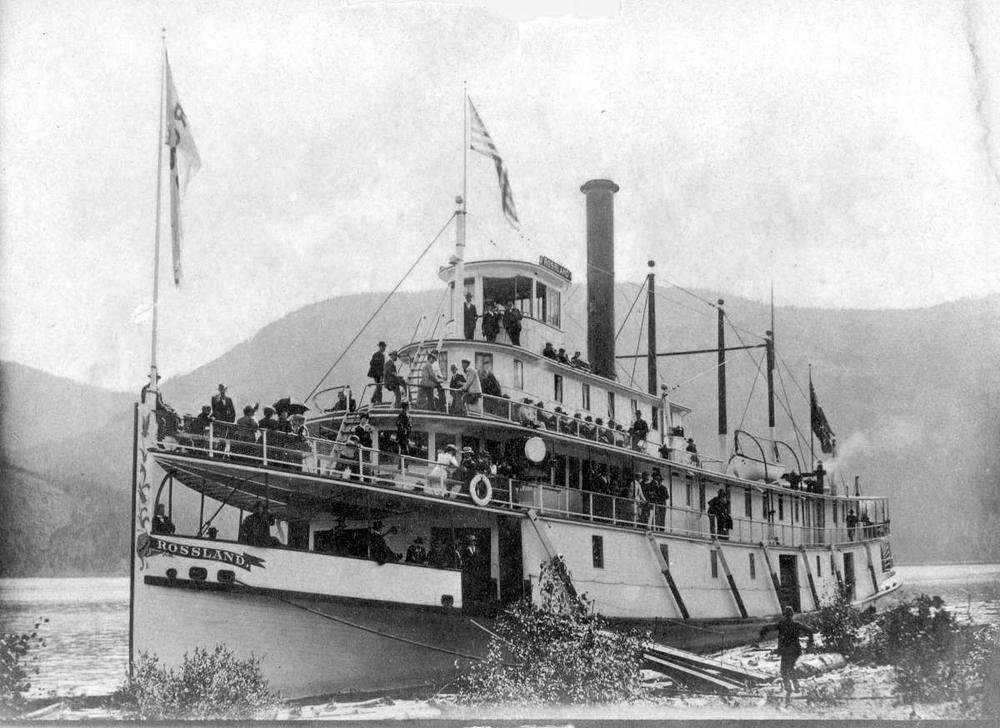

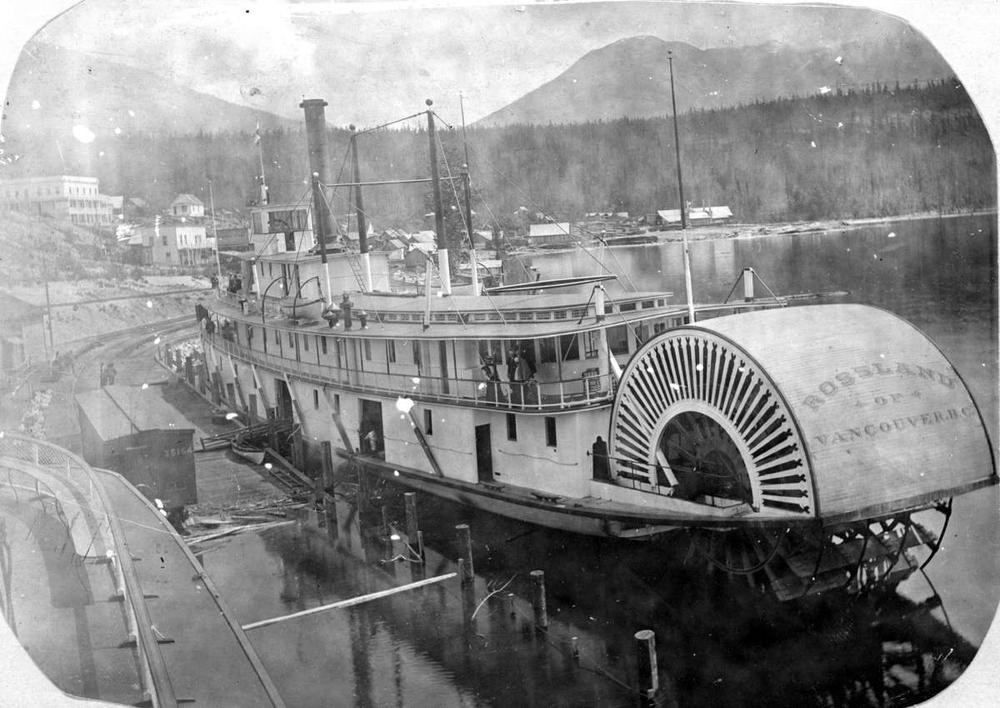

The S.S. Rossland was a steam-powered sternwheeler that operated on the Arrow Lakes and Columbia River from 1897 to 1916. The standout in a fleet of Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) steamships, Rossland was widely known for her beauty, elegance, and, most importantly, speed.

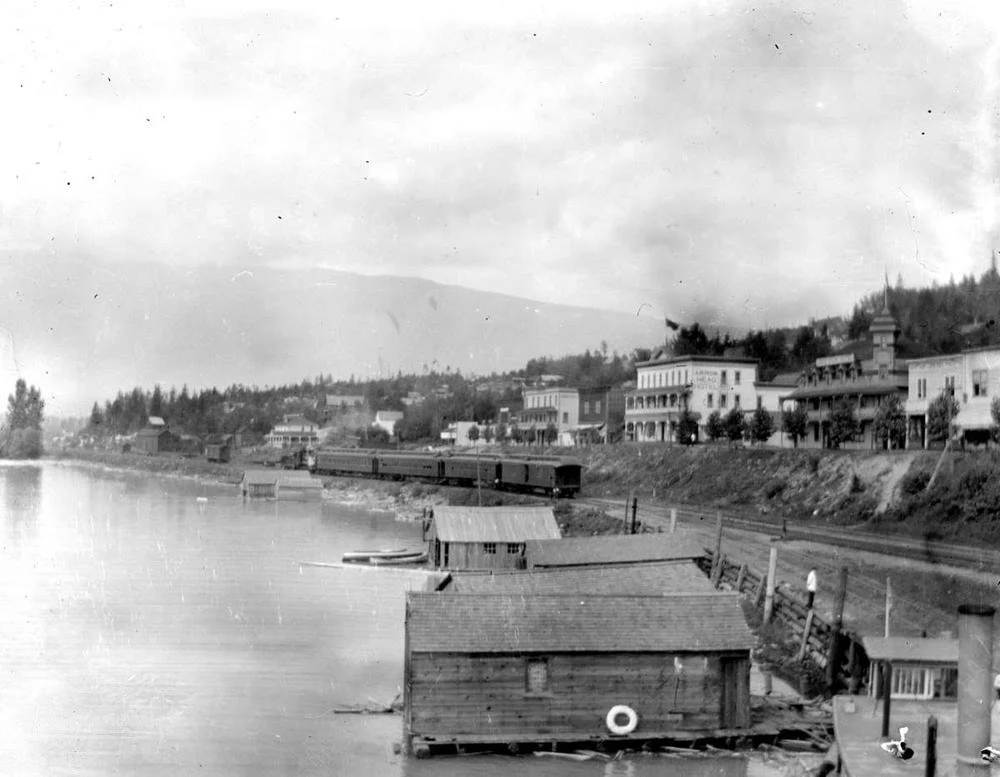

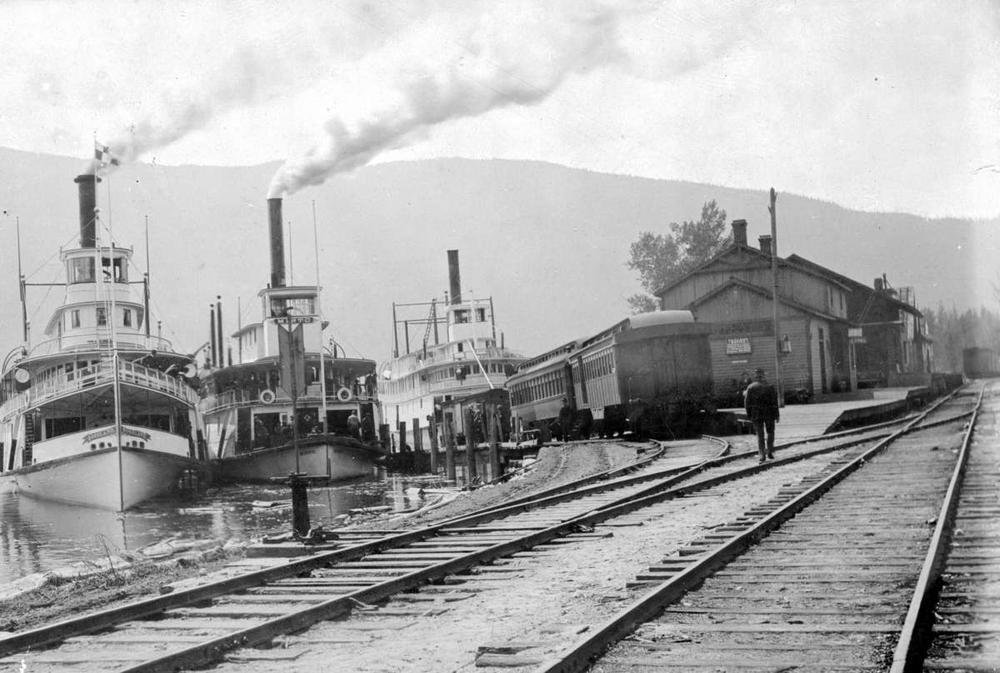

Sternwheelers were introduced to the West Kootenays in the 1880s––providing a welcomed alternative to the rigours of overland travel. Due to their sturdy construction and flat hull, sternwheelers were able to operate in fast-moving, shallow water, making them the perfect vessel to navigate the Arrow Lakes and Columbia River. The Columbia and Kootenay Steam Navigation Company was the first to monopolise the lucrative industry. Founded on December 21, 1889, the company provided a Kootenay-based sternwheeler service until it was purchased by the CPR on February 1, 1897. Upon the purchase, the CPR announced the development of a brand-new fleet. The first vessels constructed by the CPR were Kootenay, Slocan, and Rossland, named, of course, after the local mining districts of the era.

Built at the Nakusp shipyard, Rossland was launched on November 18, 1897, and was deployed as a freight vessel. Upon the sinking of Nakusp on December 23-24, 1897, however, Rossland was re-fitted as a passenger vessel and replaced Nakusp’s Arrowhead to Trail route. Then, in April 1898, Rossland began the summertime route from Arrowhead to Robson, which she would faithfully continue for the remainder of her service. Due to her powerful engines, provided by Vancouver-based BC Iron Works, Rossland was capable of reaching a high-speed of 35 kilometres per hour (22 miles) and was able to complete a round trip between the two locations in a single day, a distance of 385 kilometres (240 miles). Her passenger capacity was 300.

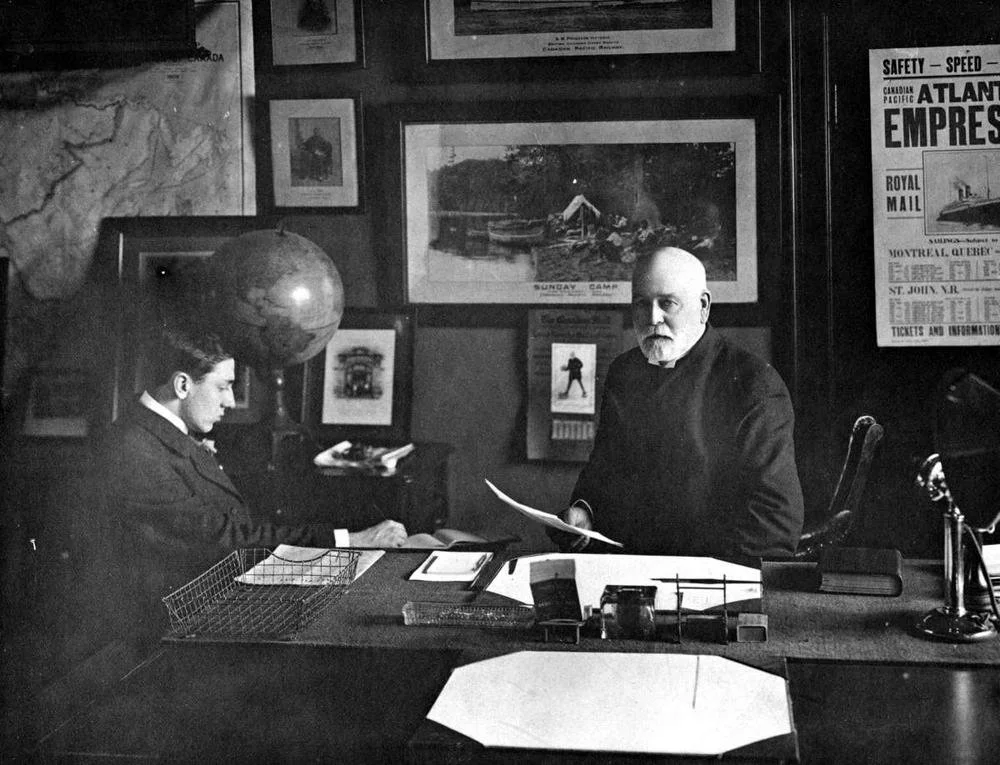

The vessel was designed and built by James W. Troup and Thomas J. Bulger, renowned steamship men from Portland, Oregon. Both Troup and Bulger were fundamental in the development and expansion of sternwheeler travel in the area. While Troup served as the General Superintendent of the CPR Lake and River Service, it was Bulger, who, as foreman of the Nakusp shipyard, oversaw the construction of the sternwheeler fleet. An April 7, 1901, edition of the Nelson Daily Miner called Bulger “. . .the best known steamboat constructor in the Kootenays. . .” and praised his role in the construction of Rossland, Trail, Nakusp, Columbia, Minto, and Slocan. Upon Bulger’s retirement in 1903, his son, James M. Bulger, succeeded him as the foreman of the Nakusp shipyard, later becoming the foreman of the Nelson shipyard.

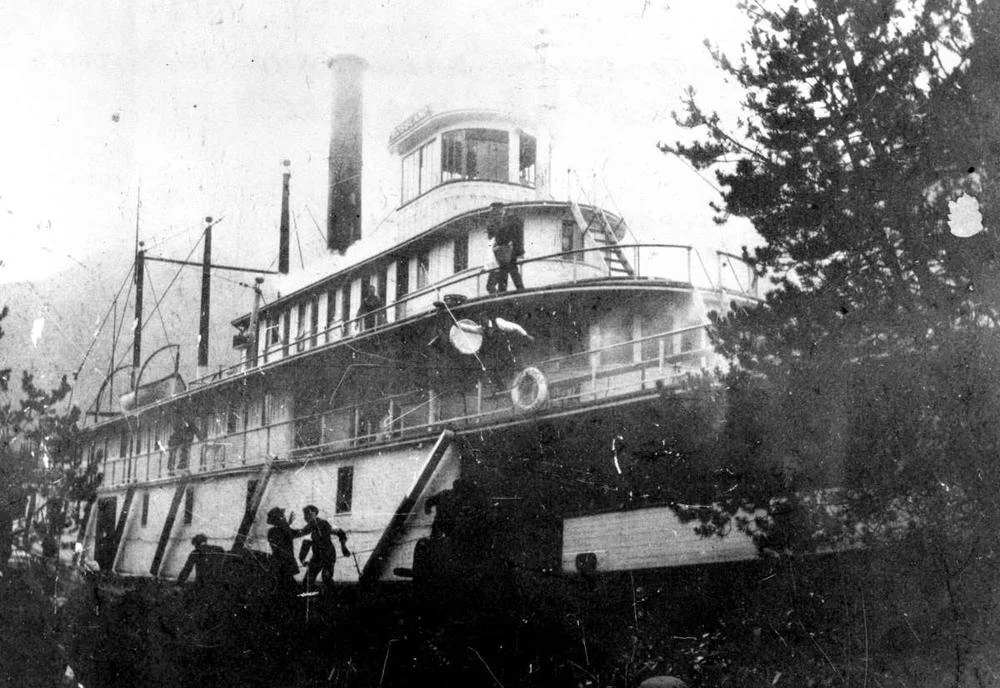

Rossland's career was not without excitement. On August 23, 1899, as the steamer was en route from Arrowhead to Robson, smoke was detected from the upper deck—signalling a fire. As the flames became visible, Captain Albert Forslund beached Rossland at the nearest shore and forced the passengers to disembark. The crew then began to douse the fire with water until it was successfully extinguished. After, the passengers were led back aboard and the vessel steamed forward—only delaying Rossland for a brief period of time. The passengers later wrote a tribute to the ship’s crew in the Nelson Daily Miner, praising them for the “. . .able and effective manner in which Capt. Albert Forslund, Chief Engineer Fyfe, Purser Taylor, and the officers and crew of the S.S. Rossland conducted themselves in combating and extinguishing the fire. . .” Although Rossland survived this incident, other vessels in her fleet were not as lucky. Trail, for example, “burned to the water’s edge” less than one year later on June 1, 1900.

Rossland received a number of upgrades over the years. In 1909, due to a predicted increase in summertime travel, both Rossland and Kootenay underwent renovations, and a number of additional staterooms were added, increasing their passenger capacity. In 1910, Rossland’s wooden hull was in need of repair. Instead of a simple rebuild, a decision was made to replace the hull entirely, which gave Rossland “an even more graceful appearance.”

On January 25, 1917, Rossland’s storied career was brought to an end. While moored at the CPR shipyard in Nakusp, where she had been since 1916, Rossland sank due to an overload of ice and snow. The immense weight caused the ship to tilt on her port side and become submerged by the frigid water. Rossland’s watchman was on board at the time, but escaped without injury. In March 1917, Rossland was raised from the water and an attempt was made to salvage the vessel––to no avail. Albert Forslund, her former captain, allegedly purchased the hull and used it as a wharf at his nearby property.

With the expansion of railways and highways, sternwheeler travel became increasingly obsolete. By the 1930s, Minto was the only operating sternwheeler on the Arrow Lakes. She, however, continued her route until April 1954, when the CPR officially announced her retirement, citing low passenger numbers and a loss in profits. In-service since 1898, Minto was one of the last-surviving relics of pioneer life and many protested the CPR’s decision. Although an attempt was made to preserve the vessel, Minto was set ablaze and discarded at Galena Bay in 1967. Today, only a handful of CPR sternwheelers survive, including Moyie, believed to be the oldest surviving passenger sternwheeler in the world. The vessel is located in Kaslo, BC, and is a National Historic Site and year-round museum operated by the Kootenay Lake Historical Society.

Written by Tyler Bignell