The Consolidated Mining & Smelting Company records of the War Eagle Mine production from 1905 to 1928. (click for a closer look!)

The Superintendent’s Office

The superintendent’s office found on the upper bench of the Rossland Museum & Discovery Centre’s grounds is a reminder of an important yet often overlooked aspect of mining: the business and administration side. Superintendents worked to ensure the smooth operation of their mine, keeping track of the rates of production, organizing labour, as well as negotiating with investors and stockholders. Working in the superintendent’s office was the only place in the realm of mining where women were allowed to work (superstitious miners believed they brought bad luck if they were to enter the mines). The work of men and women above ground, in offices such as the Superintendent’s, was integral in the formation of the Rossland mines, and early business and markets in general.

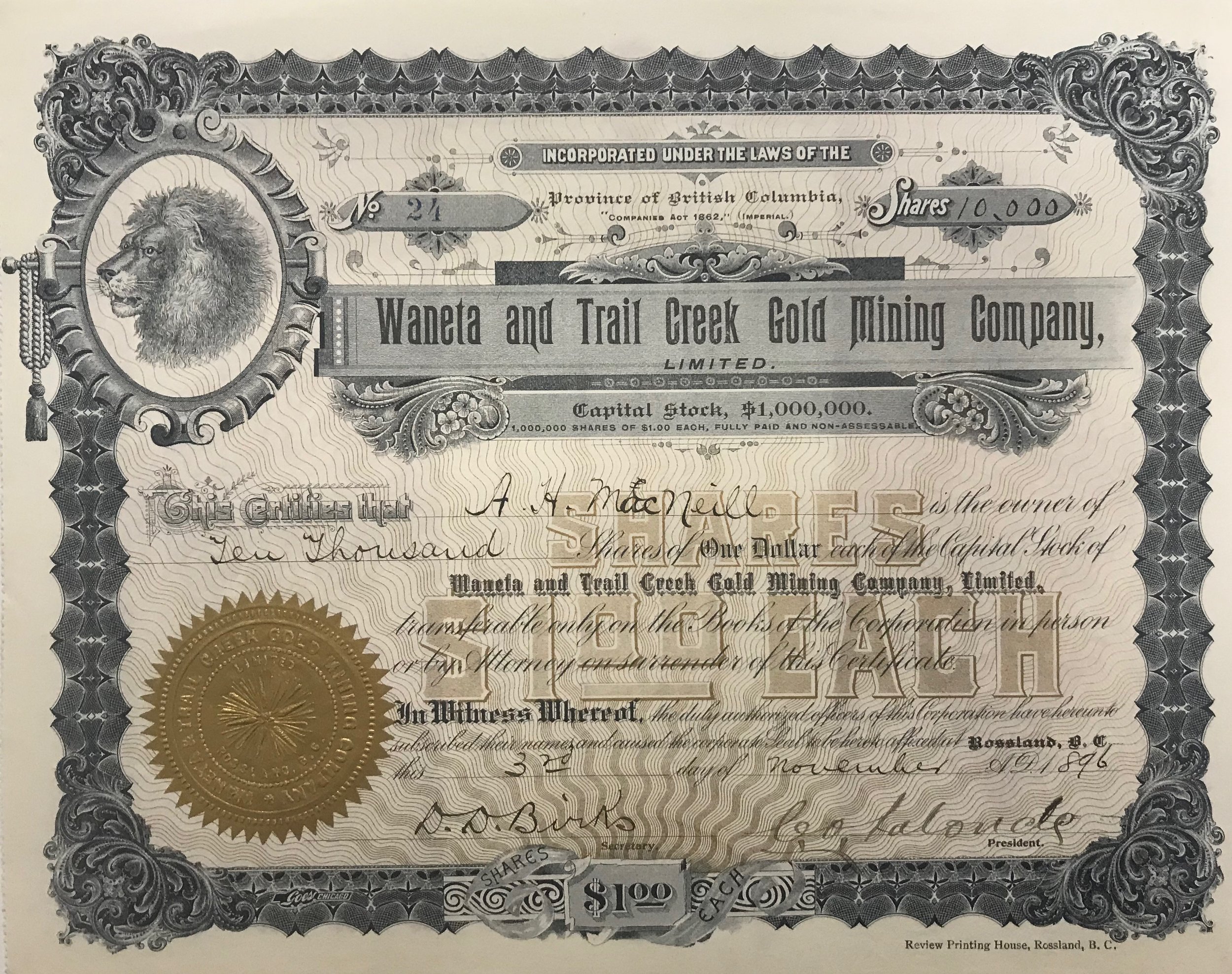

An 1896 certificate confirming A.H. MacNeill as the owner of 10 thousand shares, valued at $1 each, in the Waneta and Trail Creek Gold Mining Company. While many investors made a fortune, some less savvy businessmen were also duped by fake mining companies, which capitalized on the mining frenzy to sell shares for fraudulent mines before skipping town.

Rossland’s Role in the Stock Market

The gold boom in Rossland and the promise of riches led to a large increase in the amount of interest and desire for startup capital with so many entrepreneurs hoping to open the next profitable mine. Many investors were also eager to try their luck investing in the mines after seeing the Le Roi mine shares go from 50 cents a piece to $40 in less than a year. However, Canada’s Toronto Stock Exchange, established in 1860, felt the nature of the industry made it too risky to be involved with, and thus chose not to open investment in mining. As such, the smaller Toronto Stock and Mining Exchange was founded in 1896 with 25 members, many of which with ties to Rossland, in order to accommodate the investors interested in the Rossland mines. Merging with a rival exchange company in 1899, the organization became known as the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange and managed to thrive off the tumultuous mineral booms throughout the country becoming a main competitor of the Toronto Stock Exchange. When the Great Depression hit and many US stock exchanges turned their backs on their customers, the Toronto Stock Exchange vowed to uphold their promises to their customers despite the financial difficulty. This decision led them to very difficult times, and in 1934, they merged with their rival competitor the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange allowing both parties to survive the hungry 30s. As such, the mines of Rossland, in their own small way, contributed to the growth and survival of Canada’s main financial institution, the Toronto Stock Exchange.

A map of the mine claims of the Rossland area, circa 1923. Note how many bike and ski trails have gained their names from these stakes! (Click for a closer look)

Mine Claims

An important aspect of the bureaucratic side of mining is the process of staking mining claims. Mine claims permit a prospector/company to extract the minerals from the claimed parcel of public or crown land. This did not give them exclusive rights to use the surface land but allows for the development of mining operations and the extraction of accessible minerals. Over 2000 claims were made in the greater Rossland area, however, roughly 96% of the ore produced came from just three of these mines: the Le Roi, the Centre Star, and the War Eagle.

Moris, Bourgeois, and Topping

The first claims in Rossland were made by two men by the names of Joe Moris and Joseph Bourgeois, who had heard rumours of great possibilities for gold within Red Mountain. Travelling the Dewdney Trail, the two men staked 5 claims on the mountain in the summer of 1890, taking 10 samples to be assayed in Nelson. Only some of the core samples showed much promise, but the men decided to register their claims and try their luck anyway. Unfortunately, they faced a few obstacles, the first being that the laws of the time only allowed a prospector to stake 2 claims maximum, and the second that the registration fee was more than they could currently afford. As such, the duo struck a deal with the assayer they had hired, Eugene Topping, wherein he would pay the claim registration fees ($12.50 total), and in exchange, they would give him one of their claims - the “Le Wise”. Topping accepted the deal but renamed his claim the Le Roi. Topping turned out to be a very lucky man, as the Le Roi claim and subsequent mine became the most profitable of all the Rossland mines. However, Moris and Bourgeoise could hardly complain, as their two claims both became worth roughly $15 million within the next 5 years.

The “Memoirs of Angus Davis” were completed shortly before the death of the author on January 24th, 1949. They will be published in serial form through subsequent issues of “Western Miner.”

No mining engineer commanded greater respect nor gained more popularity in British Columbia than the late Angus Davis. Upon his graduation from McGill University, he proceeded to the Rossland gold-copper camp and, with the exception of his meritorious service overseas in World War 1, spent the rest of his life in British Columbia. During his career he managed mining operations in all parts of the province and at various times engaged in consulting practice. He was equally well known to prospector, miner, operator, and promoter.

Continue the Outdoor Tour: